King Qaa (also written as Qa’a) lived around 3100-2890 BCE. He was also called Kaa, and had a cartouche name Qebeh. His father was most likely Semerkhet.

According to Manetho Qa’a reigned for 26 years, though he calls the king with the name Bieneches. The conclusion that these two names mean the same king comes from the seal impressions of Hotepsekhemwy, who was Qa’a’s successor. Manetho mentions Hotepsekhemwy as the successor of Bieneches.

There are other estimations for is rule: 33 years, based on several stone vessels mentioning Qa’as second heb sed festival. Usually heb sed’s are celebrated for the first time after 30 years of reign, after that every third year.

Turin king list states that his rule lasted for 63 years, which seems unlikely. Still there are a large number of mastabas built in Saqqara that date to Qa’a’s reign, which points to a long reign.

Qaa performed several cultic activities - these are mentioned in year labels. There is a mention of the foundation of a religious building called qA.w-nTr.w. A rock inscription in the south of Egypt, in Elkab, suggests there was a mining expedition in Egypt’s Eastern desert during Qa’a’s reign.

An ivory gaming rod was found in Saqqara that shows an Asiatic war prisoner with his hands tied behind his back, the king victorious over him. This may be a sign of a real military campaign or might just as well be symbolic -the pharaoh was always shown victorious over his enemies in art. This depiction and vessels of Syria-Palestine suggest there was definitely contact between the two cultures.

After Qa’as death there is evidence of fighting for the throne. Possible participants were Sneferka (who was mentioned as king in the tomb of the official Merka. In Merka’s tomb is also a stela where the second heb sed is mentioned), Ba and Hotepsekhemwy (who won the crown). So there may have been a short period of unrest after Qaa’s death.

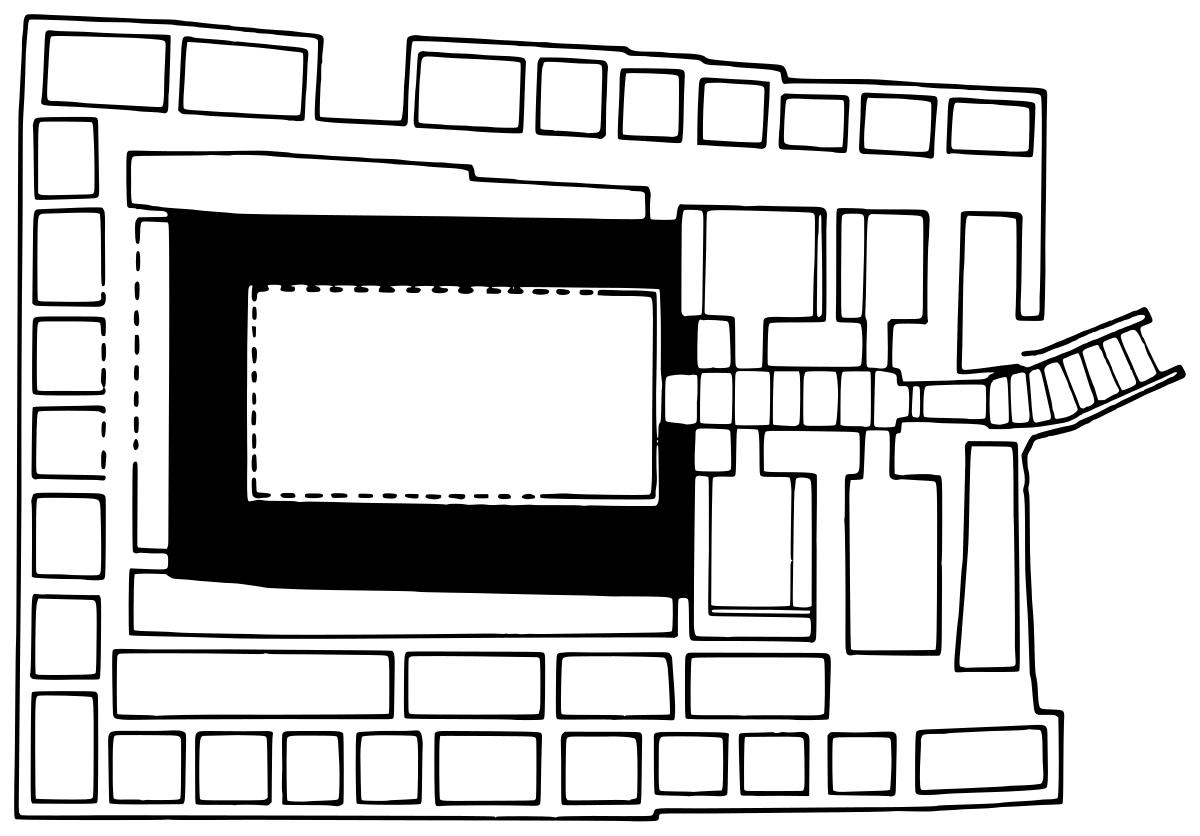

tomb of qaa/ qa'a in abydos/ tomb q

By Josiane d’Este-Curry, according to W. Kaiser and G. Dreyer - Dieter Arnold: Lexikon der ägyptischen Baukunst, Patmos Verlag, 2000, S. 11, Public Domain, Link

By Josiane d’Este-Curry, according to W. Kaiser and G. Dreyer - Dieter Arnold: Lexikon der ägyptischen Baukunst, Patmos Verlag, 2000, S. 11, Public Domain, Link

Qa’a had his tomb built nex to Semerkhet’s and Den’s. That seems to indicate he was related to these kings

The size of Qa’a’s tomb is impressive (98.5 X 75.5 feet or 30 X 23 meters). It had 26 sacrificial burials around it. The tomb was built in several stages, and there were long periods of interruptions in the building work, which speaks of a long reign.

Hotepsekhemwy’s seal impressions were found near the entrance of the tomb, and this could be a sign that Hotepsekhemwy was Qa’a’s successor who completed Qa’a’s tomb. or at least performed cultic activities there. This act may be a sign of him legitimizing his rule. Hotepsekhemwy’s name also may give a clue he won the crown - it means “The two powers are at peace”.

Manetho writes him as the successor, and the first king of the Second Dynasty of ancient Egypt. Why Manetho decided that the first dynasty ended with Qa’a and a new one began with Hotepsekhemwy, is unclear. There is the fact, though, that the first kings of the second dynasty prefer Saqqara for their burials instead of Abydos. Could it be that they had ties to northern Egypt? Also the retainer sacrifice burials end with Qa’a. So there seems to be some kind of a dividing line between the first and second dynasties.

A limestone stela found in the tomb shows Qa’a wearing the White Crown, being embraced by Horus. His name is in a serekh, and the White Crown of Upper Egypt is part of the king’s name. The stela is now in the Louvre.

Two typical royal funerary stelae were found on the east side of the tomb.

Also from the tomb comes a seal-impression with king list of the names of the first eight kings. Narmer is the first name in the list, which marks him as the founder of the dynasty. After him come Aha, Djer, Wadj, Den, Anedjib, Semerkhet and finally Qa’a. Queen Merneith’s name was not mentioned in the list, which seems to confirm she was not considered a pharaoh, but a regent for Den until he came of age to rule.

Qa’a Abydos tomb was excavated by Emile Amelineau in the 1890s, by Flinders Petrie, and by Werner Kaiser and Gunther Dreye in 1991. The later excavations found 30 inscribed labels that tell us of delivery of oil of berries or tree resin, probably from the Syria-Palestine region.

The tomb appears to have been altered through times. Only the brick built substructures have survived.

Back to Homepage

Back to Pharaohs Main Page